Stories from the Past

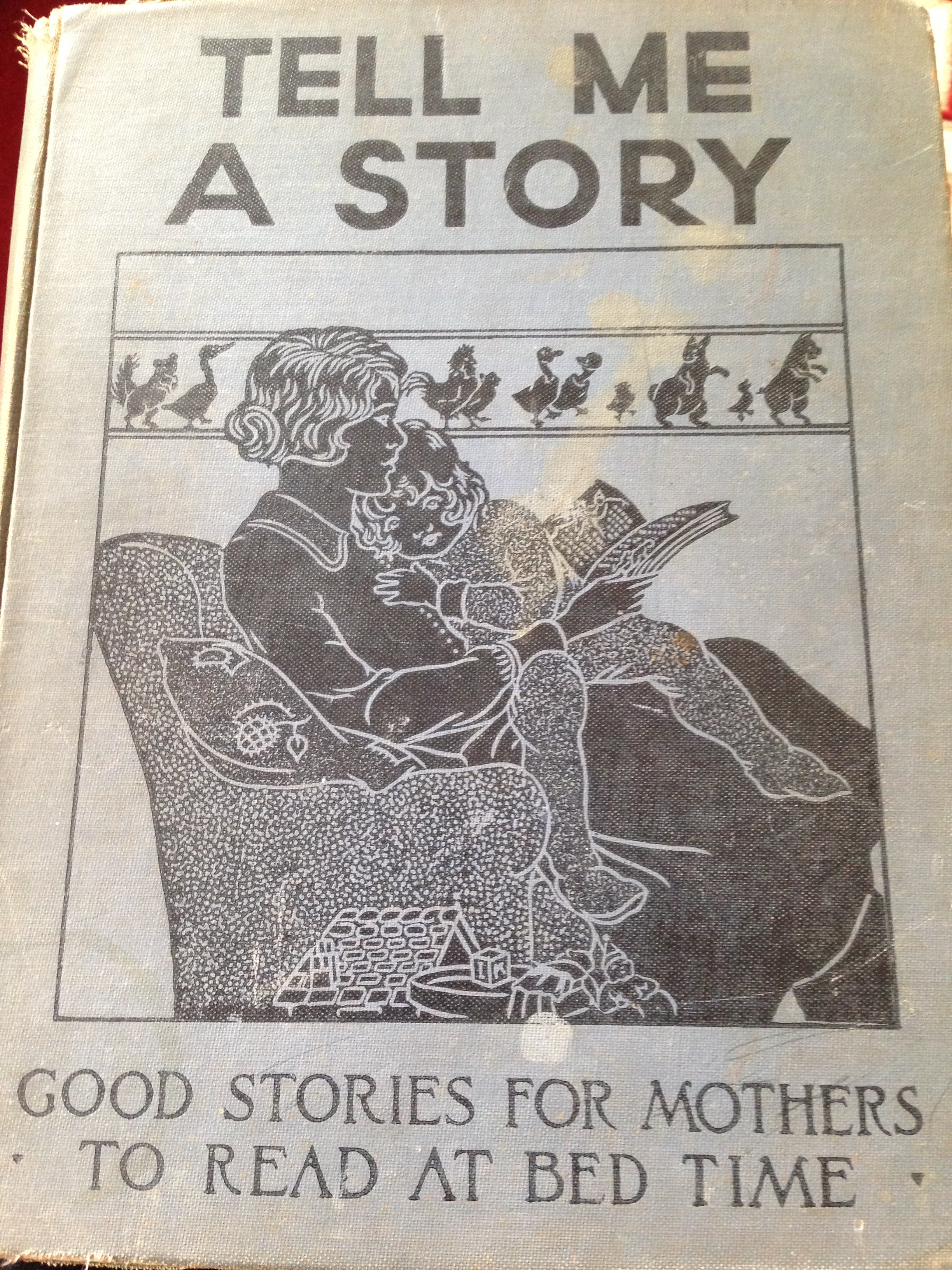

This book was sitting on a stool outside of a second-hand store calling to me. It was published in 1932 (there were four copyrights, and ’32 was the most recent). The name of a onetime owner—the last?—is Eulalia M. Cunningham. (I’ve heard of Eulalie but not Eulalia—lovely name. Lilting.) Her name is written on the copyright page, along with the words “Christmas 1944.” On the front page, in a more childish script, Eulalia herself (I’m guessing) wrote, “E. Cunningham, and then, having realized she forgot something, “E.M. Cunningham.” She added a Christmas sticker to the page, just the way a child would—it’s randomly placed on the left side of the page, toward the bottom—just where it happened to come off her fingers. A man and a woman in a sleigh, with a Christmas tree sticking out the back. Just think—a seventy-two year-old sticker!

The title page says the stories are selected from John Martin’s Book, which was a popular children’s magazine, aimed at five- to eight-year-olds, published from 1912 to 1933. (Thank you, Google.) John Martin was a pseudonym of founder Morgan Shepard. I couldn’t find any info on why it folded, but far bigger enterprises than this failed during the Great Depression. John Martin’s Book must’ve continued to resonate with readers if this book was available for purchase in 1944. (It’s not easy to find a ten-year-old book these days—not unless it’s an enduring classic.)

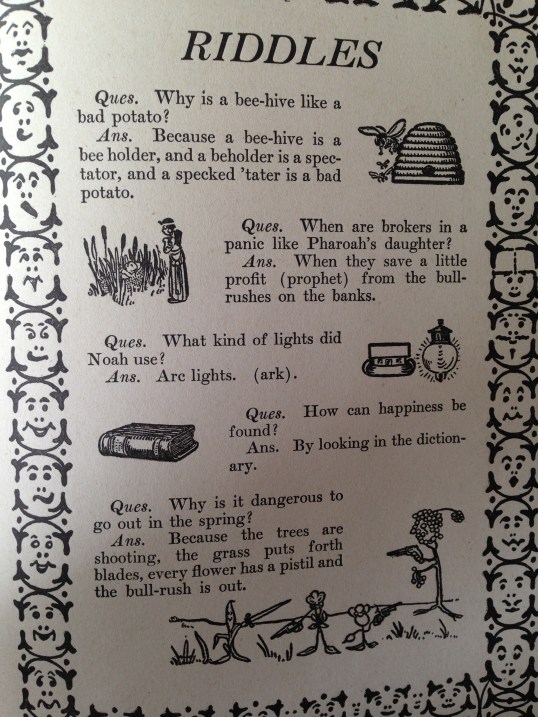

This is one dense book, with marvelous black-and-white drawings on nearly ever page. There are not just stories but poems, biographies, riddles and even pictograms.

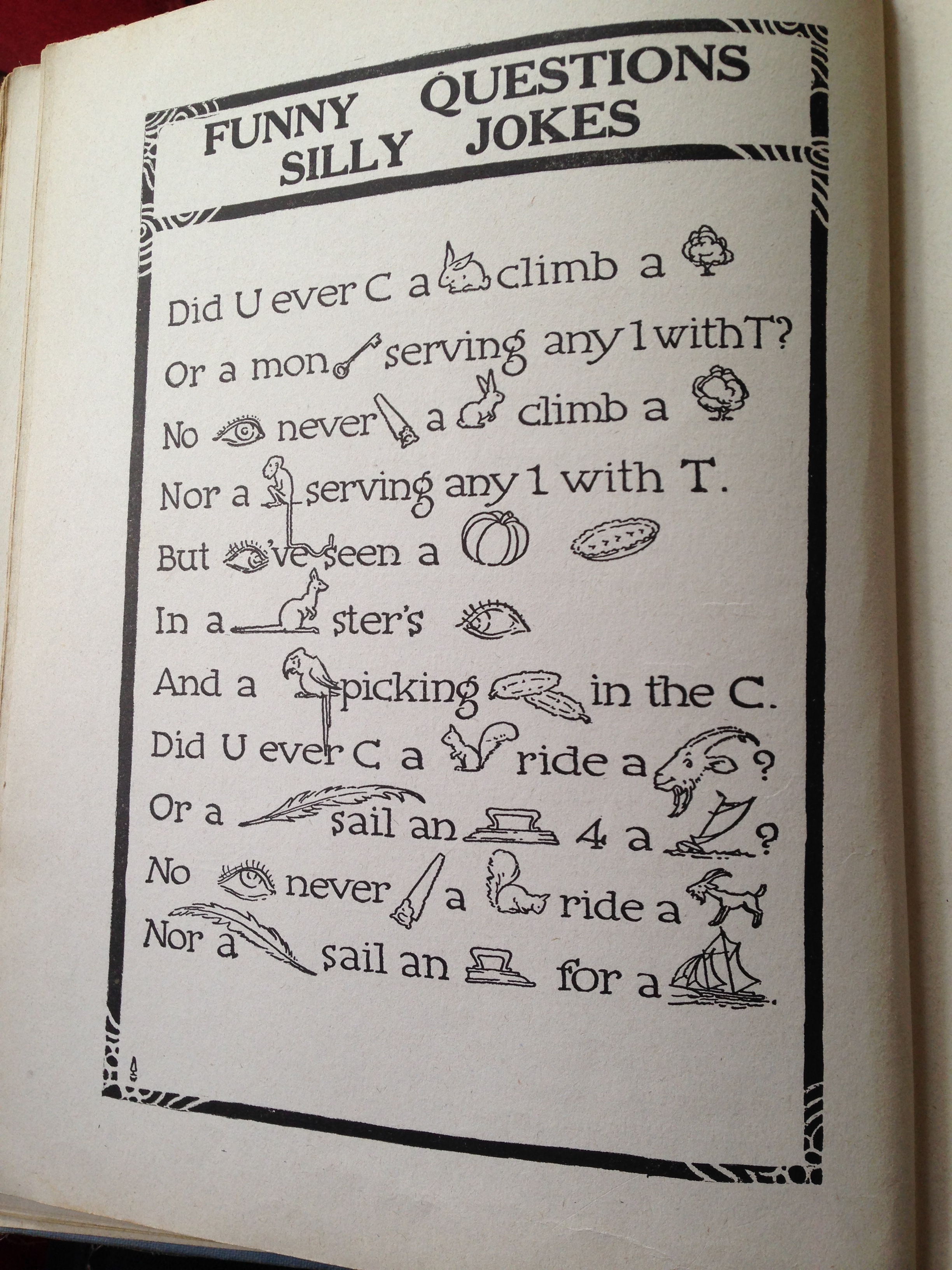

Check this out:

I can’t figure out the meaning of the line with the feather and the flat iron. A feather sail an iron for a ship?

Riddles! These are kind of complicated. And a bit weird. Hats off to the five- to eight-year-olds who are getting these:

There’s always something about stories from past eras that startles or even shocks. In a few of the stories here, people get hurt, and good. “Tommy Elephant Discovers the Railroad,” a monkey named Fibber-Jibber convinces Tommy that a strange creature running along a new jungle trail wouldn’t dare hurt as large an animal as Tommy. So Tommy stands on the train tracks, in front of an oncoming train. Yikes! He gets hit, naturally. There’s an illustration showing the elephant, head over heels, while the train rushes past. He’s not killed, which he surely would be in real life, but he’s badly bruised—-much to Fibber-Jibber’s amusement. It’s hard to imagine this was ever funny to anyone, but it must’ve been. Americans of the early 20th century clearly didn’t think of animals as stand-ins for boys and girls, the way we do today. At least not wild animals. (Perhaps that changed with Babar, published in 1931?) Fibber-Jibber gets a punishment of sorts. Using his trunk, Tommy hoses him repeatedly, until he’s a “very wet, but much wiser” monkey, who doesn’t play any more tricks on Tommy for a “long, long, long” time.

There’s a tale called “Catskin,” which reads much like Cinderella except there’s no glass shoe and no stepsisters, and the heroine is, yes, wearing an outfit made out of—catskin! No wonder this story has slid into obscurity. Oh, and also, the cook beats the poor girl like nobody’s business. She’s forever breaking a ladle or a skimmer over Catskin’s head. Incredibly—thankfully—Catskin is always “none the worse.” She sneaks off to go to balls, where she meets a squire (not a prince, but quite good enough). Before long she marries him and lives happily ever after. With brain damage, no doubt.

There are Grimm-like stories like this one, but many others. The variety is pretty astonishing. Origin stories, such as how corn got its ear and how the woodpecker came to be. Christian stories—St. Francis convinces robbers to change their ways. A story about Mozart as a young boy. A tale about St. George and the dragon.

I can’t say the poetry impressed me, but I am impressed with the presence of the poetry. It’s so tough to get kids to read poetry today–to give it a chance! Shepard, writing as John Martin, contributed a poem that I wouldn’t mind reading to little ones:

A Magic

One day I saw a rule hand

Rise up to strike a heartless blow,

It did not stop to count the cost,

It did not care to know.

And then I heard some gentle words;

They worked a magic, sweet and calm,

Their gentle power held that hand

So it could do no harm.

One day I heard an angry voice,

Its words would neither think no spare,

How deep they cut another’s heart

It did not know nor care.

And then your gentle words were said.

The angry voice to softness fell.

Repentance quivered in that voice

Beneath your magic spell.

Oh, it is strong, and fine, and good

To find what gentle words will do.

I’m sure that they are always best,

And bravest too—aren’t you?

I took this Saturday night, around 8:30 pm, on the corner of Clinton and Congress streets. The sidewalks were barely passable, so everyone out was walking in the streets. It was a funny thrill, walking smack in the middle of Clinton, without a car in sight, and without any of the usual street noise, except for the roar of snow plows. The magic was over by the morning; the snow plows had done their work. The cars had taken their roads back.

I took this Saturday night, around 8:30 pm, on the corner of Clinton and Congress streets. The sidewalks were barely passable, so everyone out was walking in the streets. It was a funny thrill, walking smack in the middle of Clinton, without a car in sight, and without any of the usual street noise, except for the roar of snow plows. The magic was over by the morning; the snow plows had done their work. The cars had taken their roads back.